Philippines: Meals Across the Islands

When you arrive in a new place, certain choices feel inevitable. For me, in the Philippines, that choice was Jollibee. There are over 1,500 Jollibee locations in the country, more than McDonald’s, KFC, and Wendy’s combined — a reminder that fast food can be cultural, emotional, and deeply local. I’d eaten Jollibee before, back in the U.S., but eating it here felt like the right kind of reintroduction — a return to a flavor in its hometown.

There’s a kind of efficiency to Filipino fast-food meals: protein, rice, sauce — arranged almost like a diagram of need. The sweet spaghetti tastes like something made for children, which I mean in the best possible way: joyful, unembarrassed, direct. The chicken is crisp and familiar. The burger steak feels like comfort. I was hungry, slightly jetlagged, and this meal was simple, warm, and easy — and I was grateful for all of that.

Jollibee’s delivery network is so extensive that in some cities, there are more delivery drivers than dine-in seats. Food, here, moves toward you — a reminder of how meals aren’t only eaten, but carried, shared, delivered, returned to.

The “silog” breakfast is a kind of architecture: one protein, eggs, and garlic rice. There are dozens of variations — longsilog with sweet sausages, tocilog with cured pork, bangsilog with dried fish — but the composition remains steady. Studies suggest rice makes up more than 30% of the average Filipino’s daily caloric intake, not just as food but as foundation. Here, breakfast doesn’t rush. It fills. It centers.

Moalboal was quiet in December. The ocean only a few steps away, the day already warm. I ate this breakfast the way you drink a slow breath — without needing to be anywhere else just yet.

In the Philippines, malls aren’t just shopping centers — they’re climate-controlled community squares, meeting points, refuges from heat. Nearly 80% of urban Filipinos visit malls weekly. The food courts and restaurants feel communal, unpretentious, open to everyone. This meal wasn’t remarkable in any culinary sense, and yet that’s not the point. It was the middle of a day. I was hungry. I was surrounded by families and laughter. Sometimes that is enough.

Palawan doesn’t rush. Even the food feels slower, closer to the ground. At Tiya Ising, the sisig arrived sizzling and fragrant, crackling softly under the fluorescent light. Sisig is one of those dishes that tells a story of resourcefulness — historically made from leftovers, now beloved in all its variations. The soup was mild, steadying, the kind of flavor that asks nothing of you.

This meal wasn’t dramatic; it was kind. And that counts for more than flavor notes or culinary performance.

The Badjao restaurant sits over the water on stilts, the tide moving beneath your feet.

Adobo here is slow and deep — not sweet, not sharp, just steady and salted by time. The grilled fish was simple but perfect: char, citrus, sea air that hadn’t yet fully left the skin. And the leche flan was velveted sugar — the kind of dessert that lets the meal exhale.

Badjao felt like the kind of place where you stay longer than you planned.

Where the meal isn’t just consumed — it settles into you.

Lechon in Cebu has a mythic quality. It’s often described as the best pork in the world, roasted whole, skin blistered to glass. There are regional styles, arguments, loyalties, and stories. Lechon is food that carries identity — something eaten for holidays, homecomings, and celebrations. Even ordered casually, it still feels ceremonial.

The broth alongside it is gentle, designed to soften and balance what the pork insists upon. The meal feels both heavy and grounding — like something meant to anchor you inside a place.

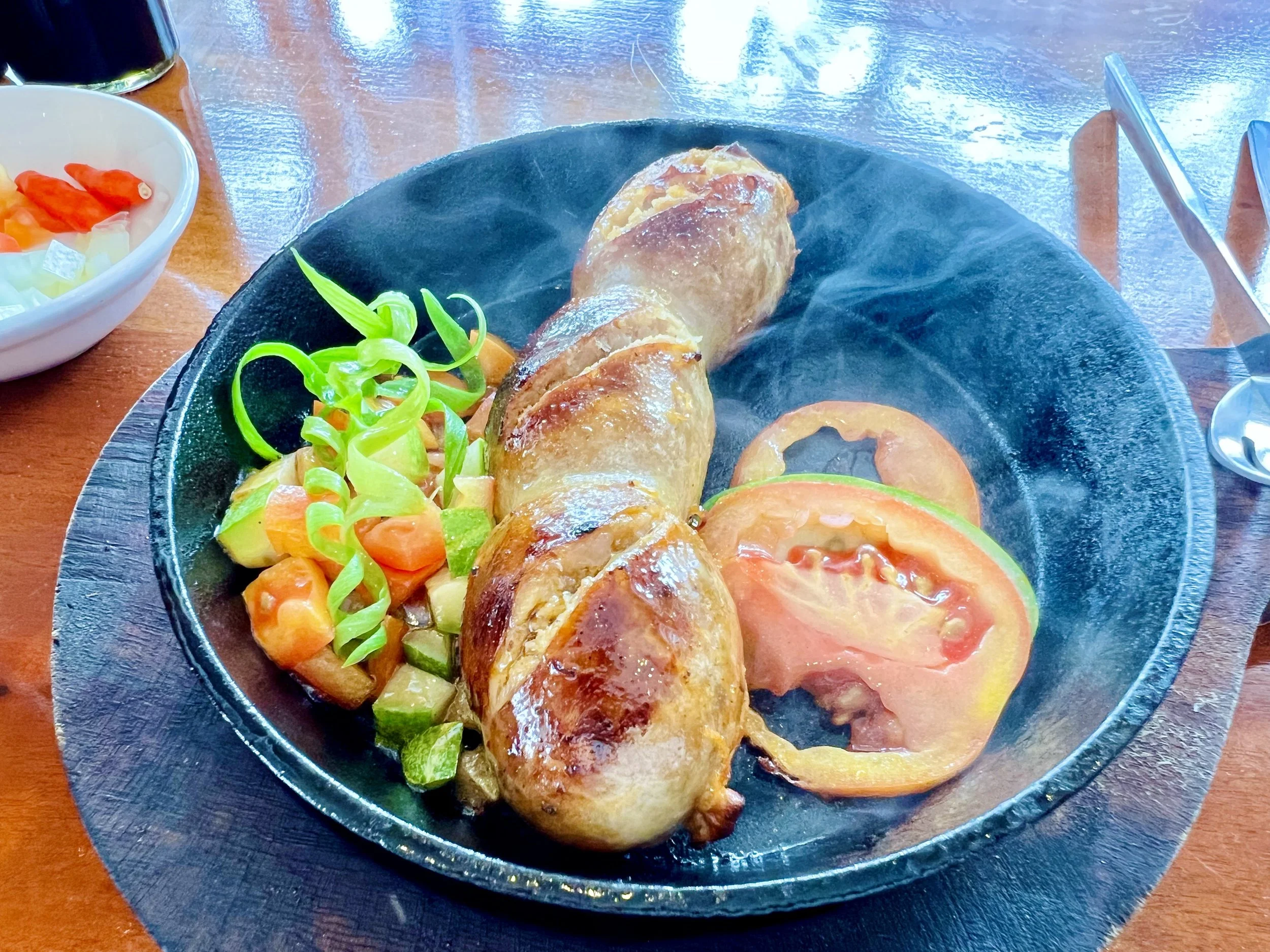

The dish arrived steaming, sound-first, smell-second — a reminder that food isn’t just taste but encounter.

I didn’t expect my final meal to be memorable. Airports are usually places of transition, not meaning. But the donut was still warm, soft with sugar, and the gelato tasted unexpectedly delicate — like someone had taken the time to care. Maybe endings don’t need to be dramatic. Maybe they just need to be gentle.

Travel changes the way you eat — not always by introducing new flavors, but by letting you meet familiar ones in unfamiliar places. Rice becomes anchor. Fried chicken becomes memory. Breakfast becomes pause. Sweetness becomes goodbye.

The food I ate in the Philippines was sometimes simple, sometimes indulgent, sometimes just convenient. But every meal was part of the rhythm of being there — hungry, curious, present.

And that was enough.

To see more photos & videos from my travels visit the links below

happy traveling,

~Sean